Getting Enough Protein?

The easiest way to check your protein intake.

This week’s post is the type of post I would usually put in the paid subscriber section. It has references and science and it took a lot of time to properly research it and put it together. This is typical of the paid-subscriber posts. This week, I decided the paid post would be for everyone, so all my free subscribers can see what they’re missing. Hope you enjoy it!

Am I Getting Enough Protein?

Rather than fight against the most frequently misunderstood topic in all of veggiedom, I’m going to embrace the protein question and provide a helpful and easy formula you can use to calculate your protein intake.

This story went deeper than expected, and is now filled with intrigue, greed, and corruption. Who knew protein was so spicy? But first, let’s get a few basics down.

“Protein” is not a synonym for “meat”

Vegetables have protein

The Reference Daily Intake (RDI) of protein is 10% of your daily caloric intake

Everyone needs protein

No one needs animal protein

So first the simple formula, then the intrigue. Food labels make it seem harder than it is, by first telling you 10% of your daily calories should come from protein, and then by giving you the food’s protein content in grams instead of calories. Confusing much? But here are the only things you have to remember to make this easy for the rest of your life:

Each gram of protein contains 4 calories.

10% of your total calories should come from protein.

So let’s say you’re an average person, moderately active, and you eat about 2000 calories a day. 10% of 2000 calories is 200 calories. Easy, right? Move the decimal left one space to get 10% of any number. So you need about 200 calories per day to come from protein.

Since we know protein has 4 calories per gram, we can convert calories to grams by dividing by 4. 200 divided by 4 is 50 grams. So we’d want to shoot for about 50 grams of protein per day.

If you’re a body builder, you might want a little more. But rather than increasing the percentage—I’d suggest increasing the total calories, which would necessarily increase the amount of protein, while keeping the percentage of the total to 10%.

Here’s why, and what most people don’t know. Every percentage point above 10% of total calories from protein, increases the cancer risk. The higher the percentage of protein, the higher the risk for cancer. It’s called a dose response, and it’s been shown in multiple peer-reviewed studies. (“High-Protein Diets Associated with Increased Cancer Risk”)

Here’s another little known fact. Any amount of protein you eat in excess of the amount your body actually needs, is stored as fat. Exactly the same thing happens with carbs. Anything you eat in excess of what your body needs, is stored as fat.

This is not a bad thing. Fat is essential to the normal function of our bodies. We can’t absorb some vitamins without it. We’d freeze to death or boil in summer without it. We’d creak like the tin man without it. We might have to eat immediately before any activity in order to have the energy to do that activity, if we didn’t have energy stored away in fat cells, ready to jump into action.

Protein is useful, too. It builds our bodies, our muscles, and organs, and blood, and hair, and nails. But too much protein will quite literally kill us.

Protein’s “Upper Limit”

Here is the question of the day: With all the science showing that any amount of protein over 10% of one’s daily caloric intake increases cancer risk, why do the official US guidelines give us an RDI of 10% but an “Upper Limit” of 35% protein? Why would they suggest up to 35%, when repeated peer-reviewed studies have shown the opposite? (Levine et al.)

The Committee

In 1997, in their wisdom, the governments of the US and Canada created a committee to study the existing science, and use it to expand the nutritional information available to the public in order to improve our health. Here are the flaws with that committee that we’re aware of from T. Colin Campbell’s book, The Future of Nutrition (below.)

The committee consisted of 11 people, 6 of whom had ties to the dairy industry. (T Colin Campbell and Disla)

The committee chairman had been successfully sued by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, for failing to disclose conflicts of interest involving the dairy industry in previous studies. (T Colin Campbell and Disla)

One member of the committee moved on to a lucrative job at dairy giant Nestlé after the committee’s work was done. (T Colin Campbell and Disla)

These are just the conflicts of interest we know about. It would be bizarre if big meat wasn’t also working to influence the findings of this committee. In all the science the committee reviewed, not one study suggested a diet that gets 35% of its calories from protein was healthful, because no such study exists. But multiple studies the committee reviewed suggested the very opposite. There was no scientific basis for the 35% upper limit number. So why did they give it?

To figure that out, we must ask ourselves who benefits if people consume more protein? Certainly not the people who see these guidelines and decide to eat the maximum safe amount, which is what the “upper limits” purport to be. But the upper limits given are more than triple the actual safe amount.

Everyone in the business of selling protein to consumers, however, profits if we buy more of their products. Those selling protein are the meat, dairy, and egg industries, and all the protein supplement industries, among others. Big food has deep pockets, mob-like enforcement methods, and powerful lobbies in D.C. (Nestle) (<–Not the food corp.)

T. Colin Campbell, the author who literally wrote the book on the most comprehensive study ever conducted on the relationship between nutrition and cancer, The China Study, spills all the tea in his latest book; The Future Of Nutrition. I got the audio version, but I’m wishing for a physical copy so I can highlight it and mark it up and flip through in search of specific passages I sort of recall.

The takeaway

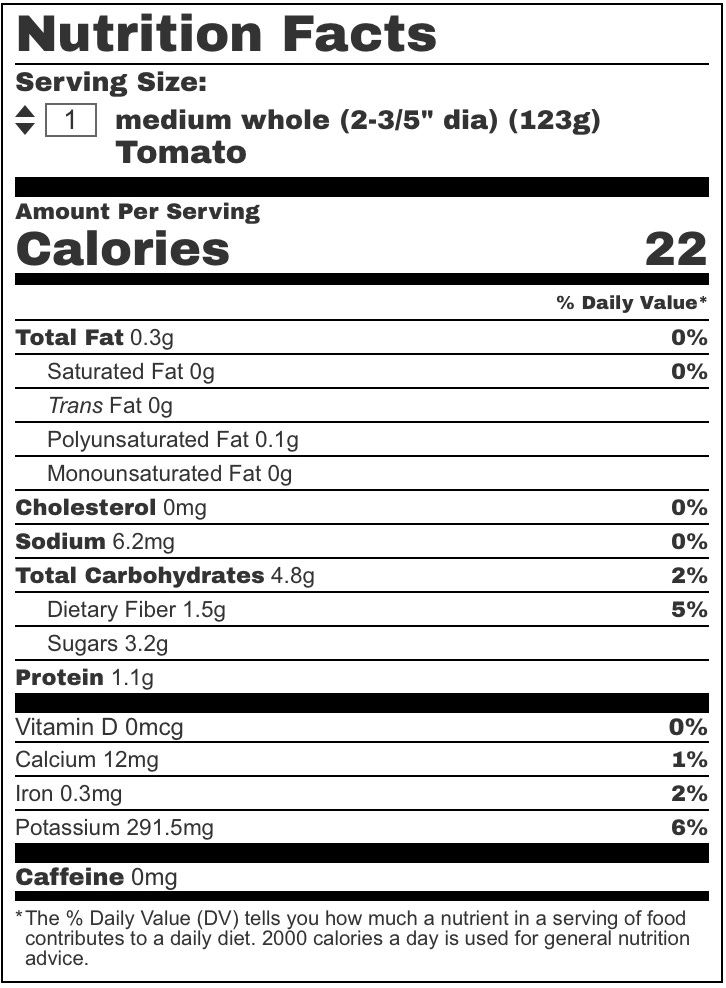

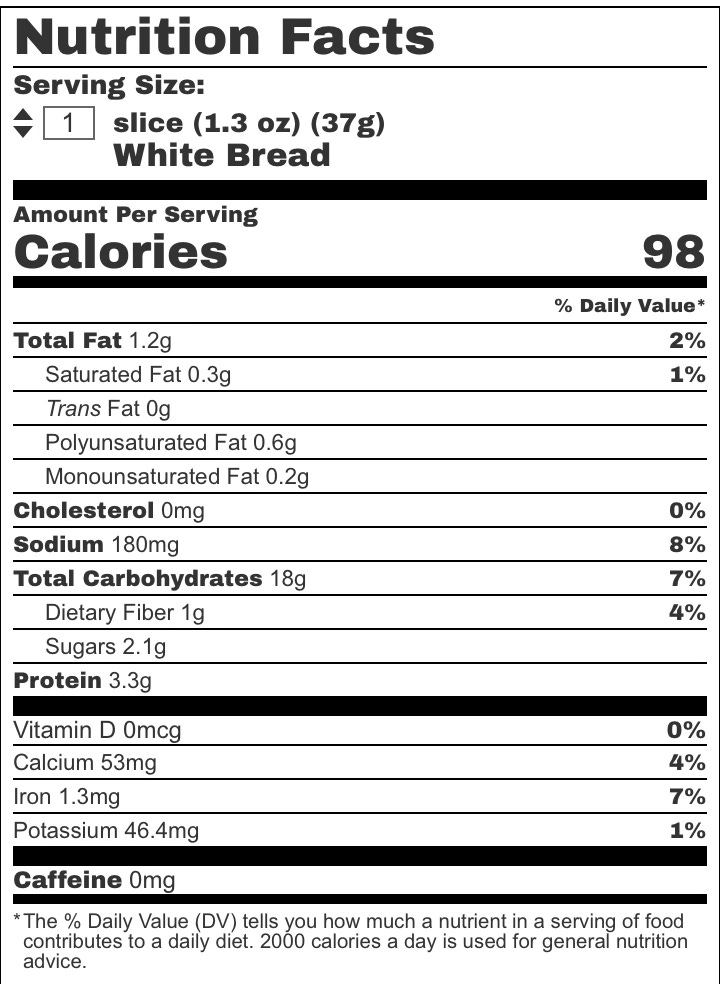

We need way less protein than we think we need, and we’re getting more protein than we think we’re getting. I recently heard from a person concerned her little niece wasn’t getting sufficient protein because she would only eat a sliced tomato between 2 slices of white bread.

It’s very easy to read food labels and calclulate your total calories, and then take your grams of protein and multiply by 4 to get your calories from protein, divide that number by total calories to get your percentage. If your food doesn’t have a label, (like almost everything I eat) you can find an online nutrition calclulator to generate a label for you.

Let’s do the tomato sandwich together.

From the labels (below,) we can see that white bread has aboout 98 calories per slice, and about 3.3 grams of protein. So the first thing we do is double those numbers, because there are two slices.

Bread, 2 slices – Calories: 196 – Protein: 6.6 grams

Then we add the info from the tomato. I made a label for that too, easy to do online. Tomato, 1 whole – Calories: 22 – Protein 1.1 gram

Now we add the two sets of numbers together. Total Calories: 218. Total Protein: 7.7 grams.

To convert the grams to calories from protein, we multiplly by 4. So 7.7 grams x 4 calories per gram = 30.8 calories from protein

Now, to get the percentage of calories from protein, we divide the calories from protein by the total calories: 30.8 divided by 218 = 0.1412844

Round it down to 2 digits, so it’s 0.14 or 14%. (Move decimal point 2 places right to convert a decimal to a percent.) See how easy?

So this little meal you would think had no protein at all, actually has 14% of its calories from protein, which is a little more than the RDI of 10% calories from protein.

Now that you know how easy it is to get enough protein, I think you can see that all the calculating and worrying are unjustified. If you’re eating a wide range of vegetables, fruits, whole grains and legumes, and eating enough of them to get full, you are almost certainly getting plenty of protein, carbs, fats, vitamins, and minerals.

You do not have to throw beans or lentils into every dish. You’re more than likely getting plenty of protein from the vegetables in the dish. If you’re concerned, run it through the Nutrition Calculator. You can enter a full recipe or one food item. (But click each item as you add it to check how they count it, because sometimes it gets weird ideas. These calcluators are really designed for brand names rather than real whole foods. I had one tell me flaxseed had about ten times the calories it actually has and it threw an entire recipe off, until I discovered the error, and entered the flaxseed separetly using nutrition info from the package.)

Add a B12 supplement daily (from methylcoblamalin, not cyanocoblamalin) and you’re golden.

Plants have protein!

Actually, they have just about the perfect amount to match what we humans require.

High Quality Proteins

One last note on the label “High quality protein” assigned to “lean” animal proteins, but not to plant protein sources. That label is based on science that shows animals grow faster on meat protein than on plant protein. At first glance, faster seems better, yes?

However, science also shows the ultimate size reached will be the same in both animals. It just takes a little longer to reach full sized on plant proteins. And science also shows that this is a good thing.

The rapid growth that happens with animal proteins is associated with cancers. I remember researching dog food protein content and learning the odd fact that lower protein levels were better for the giant breeds, because the dogs would still reach the same ultimate size, just more slowly, which is better for their muscles, their joints, their hearts, and also shows lower incidence of cancer. Turns out the same is true of humans.

I always knew we were just giant breed dogs.

The kinds of foods that nutrition science calls, “high quality protein” is actually far worse for human health than plant protein, which is not labeled “high quality,” even though it’s superior for our health. (Katz et al.)

And on that note, I have to go study biology now.

Have a wonderful weekend!

Sources Cited

“High-Protein Diets Associated with Increased Cancer Risk.” Www.pcrm.org, www.pcrm.org/news/health-nutrition/high-protein-diets-associated-increased-cancer-risk. Accessed 5 Mar. 2024.

Katz, David L., et al. “Perspective: The Public Health Case for Modernizing the Definition of Protein Quality.” Advances in Nutrition, vol. 10, no. 5, Sept. 2019, pp. 755–64, https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz023. Accessed 24 Sept. 2020.

Levine, Morgan E., et al. “Low Protein Intake Is Associated with a Major Reduction in IGF-1, Cancer, and Overall Mortality in the 65 and Younger but Not Older Population.” Cell Metabolism, vol. 19, no. 3, Mar. 2014, pp. 407–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2014.02.006. Accessed 17 Apr. 2019.

Nestle, Marion. “Let’s Talk about Food Industry Lobbying.” Food Politics by Marion Nestle, 15 Dec. 2021, www.foodpolitics.com/2021/12/lets-talk-about-food-industry-lobbying/.

T Colin Campbell, and Nelson Disla. The Future of Nutrition : An Insider’s Look at the Science, Why We Keep Getting It Wrong, and How to Start Getting It Right. Benbella Books, Inc, 2020.